|

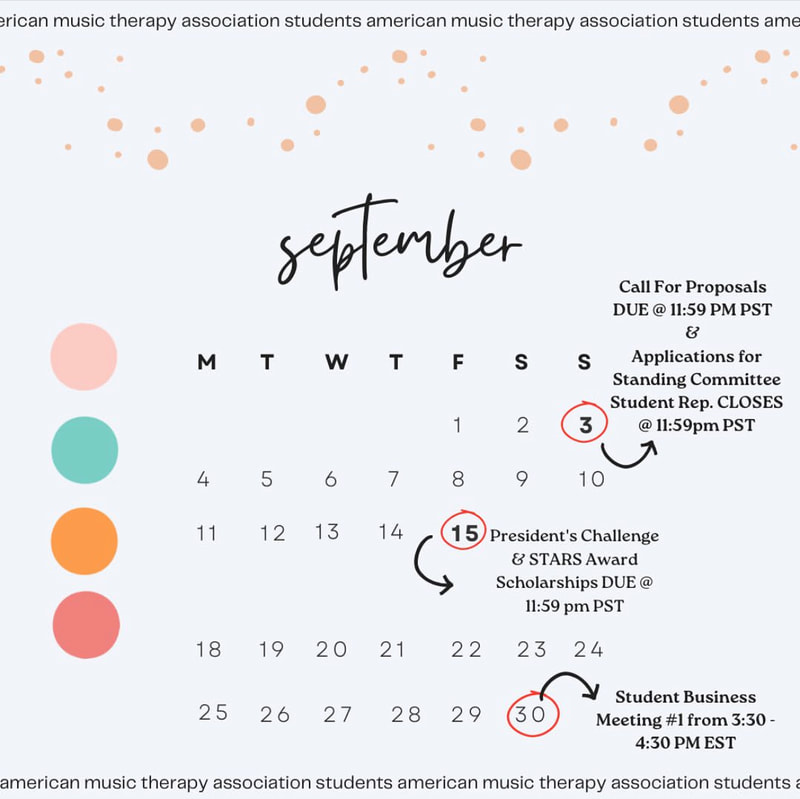

Written by Tess Vreeland, MT-BC, AMTAS Secretary 2023 It's an exciting, yet sometimes overwhelming, time to begin a new school year! Some students may be just beginning their path to becoming a music therapist as freshmen, some may be working on applying to internships, and some may be somewhere in between. Wherever you are in your academic journey, the AMTAS board would like to wish you a happy and growth-filled school year. The start of a new academic year brings potential for new opportunities to learn in the field of music therapy. Getting involved with (or starting!) your school's music therapy club is a wonderful way to form connections with peers and get involved with music therapy advocacy efforts on your campus. Consider also looking into workshops and other opportunities available through your regional music therapy associations for students. Our regional boards work hard to provide support for students and universities across the country! This fall, AMTA has provided a coupon code to assist with textbook purchases! Now through September 30th, students can input the code "MTSTUDENT2023-BOOK" at checkout to receive 25% off their AMTA published book purchase. AMTAS has some exciting dates to mark in your planners for this semester!

Staying organized is a useful skill to acquire and maintain as a future music therapist. There are resources available to help facilitate the growth of this skill, such as planners designed for music therapists. One planner available on Etsy is linked here, and it is specifically designed for music therapy students juggling practica experiences, homework, practice, and more!

Looking for some back-to-school music therapy advocacy merch? Keep looking out on our social media @_amtas_ on Instagram and American Music Therapy Association Students on Facebook for big things to be announced soon!

0 Comments

Written by Nina Stecker, MM, MT-BC

In the field of music therapy, small businesses such as private practice are constantly opening. The American Music Therapy Association (AMTA) reported that five new private practices were opened and one practice closed in the year 2020. AMTA (2020) asked participants if they were a business owner. After gathering 1,826 responses, 419 participants reported that they identified as a music therapy (MT) business owner (AMTA, 2020). There is limited current research regarding the responsibilities and activities of music therapy private practice owners. Choices concerning such responsibilities include finances, marketing, supervision, advocating for the field, face-to-face client interaction, and many more. These responsibilities influence the model of the practice and how it is administered. For my Masters thesis, I conducted a survey with 3 main research questions: 1. What were the demographics of current AMTA private practice owners? 2. How was weekly time allocated by music therapy private practice owners? 3. How was revenue generated and is it differentiated by region of the United States? The results of the survey showed that the majority of music therapists who owned their own private practice were new to the field within the most recent decades (70.2%), devoted the most of their time, on average, to direct client interaction, and offered their services to a variety of populations. Differences in average annual income varied from each region of the United States. New England had the highest average annual income at $97,500. There was a notable outlier, reporting an annual income in New England of $290,000. This survey did not inquire about practice expenses, so net income cannot be determined. AMTA (2020) reported that the average salary range for music therapy business owners was between $28,000 and $490,000. Information obtained in future surveys could include location of the private practice within the region, cost of rent and utilities if the practice had an office space, and other expenses that affected the financial responsibilities of the private practice. Overall, the data collected was beneficial for visualizing an idea of how different private practices are managed and how the responsibilities of the owners are reported. Such information may be useful to help future music therapy entrepreneurs. American Music Therapy Association (AMTA). (2020). 2020 AMTA member survey and workforce analysis. Retrieved from: musictherapy.org Written by Anna Delaney, AMTAS Parliamentarian

“The darkness only exists in the shade of the light. Your shadows will hide away once you know you are bright”. It’s rare that I manage to finish a song once I’ve started writing it. The only exceptions I’ve noticed are when they’re due as assignments for various classes or if they have a specific purpose in the near future. I often get too focused on each word, each measure, each note being absolutely perfect, not allowing myself to revise. So I’m left with a notebook of half-finished sentences, inspiration leaving as soon as it’s struck, gathering dust and lost amidst the piles of responsibilities in my life. It wasn’t until I finished my first proper song (yes, for a class assignment) that I realized how reflective the songwriting process can be, particularly as a form of insight into your own self-esteem and habits. Even more than that, though, it made me consider my journey as a student music therapist. What populations would be better suited for me, how to better avoid burnout, how to better understand my own mental state based on the themes I was writing about and genres I was exploring. And perhaps most importantly: how to process my own emotions through songwriting. To me, songwriting is one of the most vulnerable forms of creative expression. You have the ability to share your innermost thoughts and feelings through carefully shaped melodic structures and lyrical choices. I suppose that is part of what makes it so difficult for me since, even though I experience emotions very profoundly, verbalizing them can often be nearly impossible. And this realization has truly made me think: if songwriting is such a daunting task for me as a student music therapist, how much more so must it be for clients with significantly less musical experience? I have been keeping this question in my mind as I have not only continued writing songs, but as I’ve reflected on lyrics from my past, and two things stuck out to me. First, most of my lyrics tend to be incredibly emotionally charged, written during periods of intense feeling. And second, these emotionally charged pieces are always left unfinished. In my mind, this could mean that the act of writing these lyrical snippets was enough for me to fully process the intense emotions I was feeling at the time. On the other hand, though, part of me believes that the state of vulnerability needed to continue writing these lyrics is fleeting, meaning there is a strong chance they will never get finished. And that is okay. My insight through my own songwriting has made me aware of my strong tendency to strive for perfection. Whether it be through having ‘perfect’ relationships with everybody I meet, or writing the ‘perfect’ song. What I see in my writing, however, shows the self-destructive nature of my own habits, and reveals the turmoil that results from attempting to achieve an impossible goal. There is such a drastic shift between “Living your life catering to the perceptions of the rest/All the while not permitted to acknowledge your success” and “Don’t you get butterflies when you realize you’re in love with yourself?” Both of which being things I wrote within the same semester. The main difference, however, was that the second lyric arose organically when I was taking a moment for myself. Letting myself breathe. Everybody’s experience with songwriting will look incredibly different, but upon a closer look it can truly make you reconsider your perception of yourself. Songwriting can be intimidating, absolutely, but it can help make you aware of things which you otherwise might never have known. So go write a song! Or even a line. It’ll pay you back tenfold if you give it some time. Written by Tess Vreeland, MT-BC, NICU-MT, AMTAS Secretary

While music therapists’ skills are largely transferrable and board-certified music therapists are equipped to work with most populations, some vulnerable settings, such as the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), require additional training. Music therapy can be impactful for patients and families with premature infants when appropriate interventions are facilitated by an MT-BC with the credentials NICU-MT. The primary two evidence-based interventions used in the NICU are known as Multimodal Neurologic Enhancement and the Pacifier Activated Lullaby (PAL®️). Multimodal Neurologic Enhancement is a progression incorporating auditory, tactile, and vestibular stimulation aimed to increase tolerance to environmental stimuli for premature infants. This is important to premature infants due to the overstimulating environment of the NICU and the procedures they are experiencing. The Pacifier Activated Lullaby or PAL®️ is a device that uses contingent music as reinforcement to promote the development and strengthening of the non-nutritive suck. This is impactful for infants in the NICU and supports their developmental milestones. These are just two of many interventions a NICU music therapist can facilitate. In order to work with infants in the NICU, one must take steps to become certified through The National Institute for Infant & Child Medical Music Therapy. This training includes a NICU-MT class, held in person or virtually, a hands-on fieldwork component, and an exam. CMTE credits are also offered for obtaining the certification. More information can be found at https://music.fsu.edu/Music-Research-Centers/NICU-MT/ or @nicu_mt_institute on Instagram! Written by Sydney Winders, MT-BC, AMTAS President-Elect

Released in 1972, “Lean On Me” by Bill Withers, is a soulful anthem. This track is listed as number five on the album Still Bill. “Lean On Me” is categorized under the singer-songwriter, soul music, R&B, and funk genres. Lyrics to this song can be found here. In 2006, American Songwriter conducted an interview with Withers. When asked about the meaning of this song he responded, “The consistent kind of love is that kind that will make you go over and wipe mucus and saliva off somebody’s face after they become brain-dead,” he said. “Romantic love, you only wanna touch people because they’re pretty and they appeal to you physically. The more substantial kind of love is when you want to touch people and care for them when they’re at their worst,” (American Songwriters, 2021). Due to the nature of the simply beautiful melody, this message of authentic love has been uplifting many individuals. Song themes that connect to what Withers describes as “more substantial love” include support, connection, community, forgiveness, friendship, trust, and caring. “Lean On Me” is an appropriate song to facilitate a song discussion / lyric analysis of these themes. Generally, the music and meaning of this tune could be accessible to many individuals and groups. Additionally, “Lean On Me” has been known as an educational children's song and Black nationalism anthem (Genius, 2023). References Beviglia, J. (2021, August 2). Bill Withers, “Lean on me.” American Songwriter. https://americansongwriter.com/bill-withers-lean-on-me/ Bill Withers – Lean On Me. Genius. (2023). https://genius.com/Bill-withers-lean-on-me-lyrics By Sydney Winders, MT-BC, AMTAS President-Elect

Happy Pride Month! With gratitude we celebrate and support our students and professionals in the LGBTQIA2+ community. As a student community we are proud to honor all contributions to growth, innovation, and resilience in our community. We stand in acceptance as we focus on supporting the LGBTQIA2+ to celebrate pride this month and throughout the year. Below is a list of resources with information about the LGBTQIA2+ community and music therapy! Please feel free to include any helpful resources in the comments section of this blog to share with other students and professionals. LGBTQIA2+ Music Therapy Affinity Facebook Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1266098273579817/ Research Article: Annette Whitehead-Pleaux, Amy Donnenwerth, Beth Robinson, Spencer Hardy, Leah Oswanski, Michele Forinash, Maureen Hearns, Natasha Anderson, Elizabeth York. (2012). Lesbian, gay bisexual, transgender, and questioning: Best practices in music therapy. Music Therapy Perspectives, 30(2), 158-166. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/30.2.158. Informational Video: “Mindstorm Monday with Team Rainbow” by Music Therapy Ed https://youtu.be/otu0i0v-bSM Comprehensive Resource: Lee, Colin Andrew. (2022). The Oxford handbook of queer and trans music therapy. Oxford Academy. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780192898364.001.0001. Written by Sydney Winders, MT-BC- AMTAS President-Elect

For most students, summer allows for a refreshing break from classes. This is an opportune time to reconnect with self-care practices. Defined by the Global Self-care Federation, self-care is “the practice of individuals looking after their own health using the knowledge and information available to them. It is a decision-making process that empowers individuals to look after their own health efficiently and conveniently, in collaboration with health and social care professionals as needed,” (Global Self-care Federation, 2023). Taking time for yourself is an investment in your future. Use summer break to care for yourself! Self-care looks different to everyone. The National Institute of Mental Health provides multiple suggestions for general wellness with self-care such as the following:

Citation: Global Self-care Federation. (2023). What is self-care?. https://www.selfcarefederation.org/what-is-self-care U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). Caring for your mental health. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/caring-for-your-mental-health Written by Tess Vreeland, MT-BC, AMTAS Secretary

This week, we are beginning a blog series called “Research Highlights” where students and professionals are invited to promote research in specialized fields or types of music therapy practice! This week is focused on how music therapy can be beneficial to people with cochlear implants and types of interventions that may be used based on the individual’s goals. If you are interested in submitting a research blog or want to see a blog written on a specific topic, please fill out our Blog Interest Form or reach out to [email protected]! Deafness and hearing loss can occur at any stage of life, and the choice to use assistive devices or not is determined by the individual’s needs and preferences. Cochlear implants are a type of assistive device for people with profound sensorineural hearing loss. Implantation requires surgery, and the device works by sending electrodes to stimulate the auditory nerve rather than a traditional amplification of a hearing aid (Gfeller, 2001). It is a common misconception that people who receive cochlear implants do not benefit from music therapy due to the possibility of distortion of sound quality through the device. However, the multisensory nature of music therapy can be beneficial to both pre-lingual and post-lingual recipients. Music therapists can also work collaboratively with speech-language pathologists, audiologists, and other professionals to achieve various goals. Children who are pre-lingual recipients of CIs primarily focus on the goals of listening skills, speech production, and language development through movement, singing, and instrument play interventions with a music therapist (Gfeller et al., 2011). Within each type of intervention, considerations should be made to best facilitate the goals presented. Music therapists should use distinctly different instrument timbres to help with sound discrimination and listening objectives. The repetition within developmentally appropriate songs for children is beneficial to speech production and language development goals (Gfeller et al., 2011). Using musical cues to facilitate movement creates a multisensory approach that simultaneously promotes listening skills and motor-related goals. With this population, the integration of “musical elements (e.g., singing) and multisensory cues (e.g., visual and kinesthetic cues) may provide contextual cues for young children to attend to the presented auditory information more accurately” (Kim et al., 2016, p. 55). These strategies should also be applied when addressing development goals appropriate to children at this age and developmental level, regardless of hearing associated goals. Though pre-lingual implantation is popular among recipients, adults can also make the informed decision to receive cochlear implants at any point in life as an assistive tool. Prosody, the patterns of inflection in spoken language, can be addressed using music because of the linguistic correlation between music and speech (Hutter et al., 2015). While the goals of improving listening and speech skills are still relevant to post-lingual CI recipients, the social-emotional goal domain associated with hearing loss is also commonly addressed with adults in music therapy sessions. Difficulty with speech comprehension can impact socialization with others when other forms of communication are not being utilized, which can have an impact on self-esteem in social settings (Magele et al., 2022). The post-implant transition can bring frustration with the learning curve and new perception of sounds. Music therapists can address both types of goals simultaneously with intentional interventions with a multisensory approach. Music perception and appreciation can also be included as goals for adults with cochlear implants; however, the importance of this goal should be left up to the individual because music is valued differently between each person. Typically, those who benefit from interventions focused on these goals are “post linguistically-deafened adults who embrace the cultural values of hearing people, even after many years of deafness” (Gfeller, 2001, p. 91). It is important to acknowledge that many musical qualities are not transmitted well through cochlear implants, so certain musical aspects should be taken into account to best accommodate the listener’s experience. Using familiar music with more simple structures supports the client in maintaining their attention throughout interventions and connecting previous experiences with the perceived sounds. Music therapy can be a helpful tool for cochlear implant recipients across the lifespan, with specified objectives to best serve the individual’s needs. References Gfeller, K. (2001). Aural rehabilitation of music listening for adult cochlear implant recipients: Addressing learner characteristics. Music Therapy Perspectives, 19(2), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/19.2.88. Gfeller, K., Driscoll, V., Kenworthy, M., & Voorst Van, T. (2011). Music therapy for preschool cochlear implant recipients. Music Therapy Perspectives, 29(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/29.1.39. Hutter, E., Argstatter, H., Grapp, M., & Plinkert, P. K. (2015). Music therapy as specific and complementary training for adults after cochlear implantation: A pilot study. Cochlear Implants International, 16(3). https://doi.org/10.1179/1467010015z.000000000261. Kim, S. J., Kim, E. Y., & Yoo, G. E. (2016). Music perception training for pediatric cochlear implant recipients ages 3 to 5 Years: A pilot study. Music Therapy Perspectives, 35(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/miw009. Magele, A., Wirthner, B., Schoerg, P., Ploder, M., & Sprinzl, G. M. (2022). Improved music perception after music therapy following cochlear implantation in the elderly population. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(3), 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12030443. Music therapy students across America have been hard at work furthering the goals of the profession! This blog provides regional updates following the regional conferences, as well as an overview of what the AMTAS board is working on. Stay tuned for more updates and blog posts about various music therapy topics written by AMTA students! Regional Updates  Midwestern Region The Midwestern region has been working towards creating scholarship funds for more students by coordinating various fundraisers virtually and in-person throughout the year. Some of these fundraisers included a virtual songwriting competition where students could share their original content and a virtual merchandise storefront. Other in-person fundraising efforts included raffles and networking events to raise money for students to receive scholarships. These projects allowed for three students to receive scholarships in this region! Besides fundraising efforts, the MWRAMTAS board held their conference in late March. At this conference, students presented on various topics in the Passages Conference. The high attendance rates and student presenters were inspired by the executive board’s project preceding the conference that outlined the process of fully participating in regional student conferences. More updates about the Midwestern Region can be found at https://mwramtas.org/stay-conneted! Mid-Atlantic Region The students of the Mid-Atlantic region have been working hard to advocate for music therapy, connect students across the region, and give back to the community through projects and fundraisers! Various universities in this region held philanthropic events benefitting different people in their communities such as veteran associations, local schools, and children’s hospitals. In addition to fundraisers at individual universities, the region is united in a t-shirt design contest fundraiser to benefit Healing Sounds located in Virginia! This year’s MARAMTAS Passages was held in February with the theme “Back to Basics.” Presentations included a keynote presentation by Dr. Rebecca J. Warren, ``Narrative and Literature Review on Living with Invisible Disabilities.: A thesis" with Mykalia Reiter, “Music Therapy and Consistency: Building Safety and Stability for Children in Foster Care” with Anne McGoldrick, “Music Therapy and Children with Mental, Emotional, Behavioral, and Developmental Problems” with Madison Howell, "The Clinical Use of Music Therapy at the End of Life" with Elise Kohler, an Internship Fair, and “Self Care for the Music Therapist” with Dane Wagner. The MARAMTA conference was held in New York in early March, and Nazareth College and SUNY Fredonia held mini-conferences in their areas. The hard work of students did not go unnoticed as the MARAMTAS board was able to award scholarships and recognition to many individuals this year. Music therapy club awards were presented to SUNY Fredonia and Marywood University, and chapter representative awards were presented to Eliza Shriver and Lizvette Pappaterra for their outstanding work within the region. The Jenny Shin Memorial Scholarships were awarded to Eliza Shriver and Mikella Wisler, a student scholarship was awarded to Nadya Dereskavich, and membership scholarships were awarded to D'Ambra Galvin and Madeleine Berkle. Student involvement was another highlight for this region this year with 8 schools participating in a “Swap Shop” about instrumental tips and tricks, as well as the creation of a Student Conference Planning Chair position and Diversity and Inclusion committee. More updates can be found at https://maramts.weebly.com/ or @mar_amts on Twitter and Instagram! Great Lakes Region The Great Lakes region has focused on rebuilding connections between students following the pandemic through their focus on virtual events, the promotion of wellness, and their Student Passages topic of “Rebuilding Through Resilience.” Their regional project titled “The Wellness Endeavor” focused on financial, social, emotional, vocational, intellectual, and academic wellness. Financial wellness was promoted through 6 different scholarships awarded to students and 1 awarded to a university at the regional conference held in mid-March in Indiana! Vocational and intellectual wellness were promoted through presentations and panels held at the conference which included the following: “Assistive Communication Device Technology: Ethics and Possibilities with Non-Speaking Clients” by Amanda Bursch, “Piloting Your Future: Get a HeadStart on Creating a New Program” by Hannah Hunziker & Alexis Pelt, “Countertransference in the Wild” by Ariel Contreras, “Relationship Exploration Through Music: Treatment Considerations for Adolescents with Attachment Challenges” by Jaylee Sowders, and Keynote Speaker, Dr. Deforia Lane. Social media efforts were made to promote social and emotional wellness through mindfulness initiatives and virtual “connection hours” for students throughout the year. To see the wellness initiatives and other updates from this region, visit http://glramtas.weebly.com , follow @glramtas on Instagram, or Great Lakes Region American Music Therapy Association Students on Facebook! Southwestern Region The Southwestern region has worked hard to strengthen their organization to promote connectivity among students in the region! The highlight of their year was the return of an in-person conference in early March in Texas where students could reconnect, student business could be conducted, and Passages could be held. At Passages this year, more than 9 internship directors were invited to discuss their requirements and general information followed by a Q & A session. Students were active at the conference in a SWAMTAS jam session, as well as the business meetings in which a new social media chair position was created. At this conference, a Lifetime Leadership award was presented to Dr. Edward Khaler! SWAMTAS also opened applications for scholarships for students entering internship to facilitate the transition. While individual universities in this region continue to work towards individual projects, the regional executive board hopes to communicate student achievements through a quarterly newsletter to celebrate the hard work of students in the Southwest region. More updates can be found by visiting https://swamta.wildapricot.org! Southeastern Region The Southeastern region focused on expanding student involvement at the SER-AMTA conference by providing educational and scholarship opportunities to promote student involvement. Two scholarships were awarded to fund student conference registration in the region, and door prizes were provided for students attending in person. Rachel Ford, the outgoing SER-AMTAS president provided a recap of the conference experience below. More updates can be found at https://seramtas.weebly.com or @ser_amtas on Instagram! “The Southeast Region had an amazing conference in Chattanooga, Tennessee on March 23rd-25th. It was a wonderful experience for students, interns, and professionals to gather together again in person, while also online options were provided. Because our region is so large, with 19 schools spread across the southeast, conferences are a great time to learn about the education at other universities, and allow yourself to learn new things from other professionals that you may not have heard or experienced in your state. For student passages this year, our theme was formed around the idea of learning from others: Taking Charge of Your Education. As a board featuring students from 4 different universities, we wanted to create a space where students had the opportunity to share their experiences as well as voice their opinions on needs they have that aren’t being met. It was an amazing and powerful experience to see so many music therapy students, from different backgrounds and identities, all come together and be supportive, safe spaces for others. We also had two students from FSU that gave a presentation on research in undergrad. This also sparked lots of conversation and interest in the student population! As our field shifts to a new “normal”, I hope these open conversations continue to happen everywhere as we advocate for our field and our clients.” - Rachel Ford, Outgoing SER-AMTAS President Western Region The Western region has been working to provide enriching educational opportunities and scholarships throughout the year to students in this region! The regional board held online masterclasses about resources for music therapy students, internship preparation, a guest speaker event with Stephanie Leavell from Music For Kiddos, as well as a region-wide internship panel. In addition to these masterclasses, the WRAMTAS Student Connection Conference in April provided a Student Connection Panel created to support students in networking, learning, and further growth in becoming a professional. This featured Speaker Meagan Moore discussing their internship experience at MusicWorx and how internship can help shape your unique identity as a music therapist, as well as Indigo Rollins-Carlson discussing what defines resilience as a student intern through the lens of their own queer journey and their use of their end of internship project as an opportunity to create an awareness of the LGBTQIA+ community in the psychiatric setting. The regional board was also able to present 4 scholarships to students with different qualifying criteria at this conference, and they raised over $600 for future scholarships! Students were connected through a region-wide open mic night songwriting scholarship contest held in April where students were encouraged to practice embracing their creativity in songwriting and further their ability in building tailored sessions to use out in the field, and six of seven schools in the region participated. Follow @WRAMTAS on Instagram for more updates about the amazing work being done in this region! Northeastern Region The northeastern region emphasized expanding their support for universities and student involvement across the region this year. They welcomed three new music therapy programs at Westfield State University (MA), University of Rhode Island (RI), and Southern Connecticut State University (CT), which doubled the number of schools in this region! Westfield University also held a region-wide event titled, “We’re All in This Together!” that included opportunities such as improvisation, parachutes, musical chairs, GIM meditation, and songwriting activities for students to get to know each other. NERAMTAS provided other opportunities for student involvement throughout the year with their Passages conference in the fall in Massachusetts and their regional conference in the spring in Vermont. Fourteen students and new professionals presented at Passages this year on topics such as students' perspectives on music therapy advocacy, guitar skills for music therapists, addressing sex in music therapy for adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and the collaborative role of music therapy clubs in providing mental health support to students on campus. This region also held a virtual fundraiser in April that raised $850 for student conference attendance support! At the student business meeting, students voted to include a Code of Ethics for this region that emphasized the core values of music therapy students. To stay updated on news from this region, visit their linktree https://linktr.ee/neramtas, https://www.neramtas.org/, or follow NER-AMTAS on Facebook, or @neramtas on Instagram and Twitter! AMTAS Update The AMTAS board has been working in the past few months to facilitate connection between regions and music therapy students across the country! One of the highlights was during the first annual World Music Therapy Week in April 2023. The AMTAS board created social media content connecting students from across the country and world, providing historical information about AMTAS, and advocating for the profession of music therapy. The board has also worked to highlight student achievements for students in different stages of their education through social media spotlights and become more active on the AMTAS blog for students to have another platform to connect and share knowledge! AMTAS is working on fundraising projects and initiatives currently which will be promoted through the website and social media platforms. Stay updated on the latest AMTAS events and initiatives @_amtas_ on social media or at amtas.org!

President, Micah Castillo: [email protected] President-Elect, Sydney Winders: [email protected] Vice President, Lorena Gonzalez-Zeno: [email protected] Secretary, Tess Vreeland: [email protected] Treasurer, Colin Smith: [email protected] Parliamentarian, Anna Delaney: [email protected]  Written by Tess Vreeland This year marks the first occurrence of World Music Therapy Week from April 10th-15th! Declared by the World Federation of Music Therapy, this week is meant to honor and highlight the hard work and accomplishments of music therapists around the world. In honor of this celebratory week, this will be the first post of this year’s AMTAS blog. The purpose of this blog is to connect music therapy students from across the country in sharing topics they are passionate about and experiences they have had. If you are interested in participating, submitting an idea, or writing a blog post, please fill out this form (Blog Interest Form) or email [email protected]. This introductory blog is an overview of music therapy settings, goals, and interventions that are commonly used. While music therapists in the U.S. are united on the basis of the Certification Board for Music Therapists (CBMT) credential and standards set by the AMTA, each music therapist has the liberty to address individualized client goals using a variety of music therapy approaches and methods. The unique approaches and styles between music therapists highlight the creativity and drive of this research-based profession. Where can music therapists work & who do they work with? The diversity of settings that music therapists work in is constantly growing and expanding as research continues in the field. Music therapists can work with people of all ages and abilities including, but not limited to: “Children, adolescents, adults, and the elderly with mental health needs, developmental and learning disabilities, Alzheimer's disease and other aging related conditions, substance abuse problems, brain injuries, physical disabilities, and acute and chronic pain, including mothers in labor” (AMTA, 2023). Various settings such as hospitals, schools, clinics, private practice, assisted living facilities, day programs, behavioral health centers, and more can be places of employment for music therapists. What are some common goals of music therapy? Because of the multi-sensory aspect of music therapy, it is an accessible and adaptable way to reach a variety of non-music therapeutic goals. Some of these goals from the AMTA website include promoting wellness, alleviating pain, managing stress, expressing feelings, enhancing memory, improving communication, promoting physical rehabilitation, and more (AMTA, 2005). Ongoing assessment and reassessment of goals is a vital part of the music therapy process that facilitates growth in different goals depending on the needs of the specific individual. What does a music therapy intervention look like? There are four general categories that music therapy interventions fall into. These are receptive, recreative, improvisational, and compositional music therapy interventions. Receptive interventions focus on listening and experiencing music, while recreative uses pre-composed music in various ways to facilitate different goals. Improvisational interventions use “spontaneous music making using simple instruments, body percussion, or the voice” (Parkinson, 2020). Compositional interventions are structured music-creating experiences for the individual exploring different expression goals. Music therapy interventions are adapted to the current goals, preferences, and client state. Advocacy is such an important piece of being a music therapist, and world music therapy week is a global opportunity to spread information about this compassionate profession. For more information & advocacy resources, please check out the sources the information for this blog was found below! Happy world music therapy week, and thank you to music therapists and music therapy students everywhere! Sources: American Music Therapy Association (2023). https://www.musictherapy.org/about/musictherapy/ Parkinson, M. (2020, July 15). The four types of interventions in music therapy. Wellington Music Therapy. https://wellingtonmusictherapyservices.com/the-four-types-of-interventions-in-music-therapy/ World Federation for Music Therapy. (2023). https://www.wfmt.info/ PLAYLIST SATURDAY: GET DOWN WITH COUNTRY 1/10/2021 0 Comments Written by Anna Bocanegra [Disclaimer: These posts are meant to build repertoire and be a stepping stone in how to use these songs within a session. If you have used this song differently or have any other ideas for songs and suggestions use the comment section to create a discussion.] Deciding to choose the Country genre to be my first post of this series wasn't my idea, to say the least, but for someone who disliked country for quite some time, it was best to start with something I knew hardly anything about. If Country music isn't your cup of tea, this post is definitely going to be a great resource for you to start off with and broaden your horizons! As a Rising Star at Cracker Barrel, Country music is always blasting. As a Music Therapy student, I listen and observe the music closely, trying to understand how to use these songs in a session should Country music be a preference for future clientele. Though small, these few songs gathered from a Cracker Barrel playlist were deemed great use to add to a playlist and begin learning some Country tunes. Some Things I Want to Sing About by The Grascals Originally written and recorded by The Osborne Brothers (another artist you should definitely give listen to), this song has the potential for lyric substitution to get a client engaged in your session by writing about memories, things they like, or even about what is happening in their life. The instrumentation isn't on the "happy" or "sad" side of its F Major key and can definitely be on the slower side if need be. Give it a listen on Spotify! If I Die Young by The Band Perry The Band Perry created a lovely and somber song about death. Death is a major part of human life for the living with pondering thoughts, played-out scenarios, and questions. This song could be used for grieving a client's loss, existentialism, and learning to come to terms with death. Give it a listen on Spotify! Buy Me A Boat by Chris Janson This is one catchy song especially when you get to the chorus. With a catchy chorus comes a great opportunity for small-task sequencing for your client to use for everyday tasks or problem-solving. Just remember to fit your words into a proper duration of the original chorus for it to make sense musically! Give it a listen on Spotify! Now that you've got a couple of different songs to listen to and experiment with, why not broaden your horizons by searching for more Country on Spotify or any other apps you using for music. What are some Country songs you've used in session or how else can these songs be used? Comment down below! |

Hello AMTAS, my name is Mercedes Shook and I am your secretary for the 2024 year! The purpose of this blog is to provide updates on the AMTAS region, give helpful tips and tricks for music therapy students, share meaningful experiences, and promote collaboration with all music therapy students across America! If you have any ideas or questions regarding this blog please don’t hesitate to reach out via email.

Interested in writing a post? Click here to submit the Blog Interest Form. Email: [email protected]. CategoriesArchives

July 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly